|

|

Empty Nest Magazine

|

A Bowl of Cherries: Life and the Empty Nest—They’re What You Make of Them by Jewel Littenberg

Traditions of an Empty Nest My first empty nest experience consisted of waving goodbye to our only child as we drove away, until I could no longer see that small figure standing on the steps at Indiana University. I was so certain that this kid from Florida, who slept wrapped with the covers over his head in the hottest of temperatures, would ditch the cold weather by January and head home. Wrong! Wrong! Wrong! He survived it, and so did we. The next empty nest feeling came over me when our son became engaged. The closer his wedding day came, the more I began to feel that he was about to belong to someone else. I couldn’t believe the effect it was having on me! My mother, with six children of her own, had a saying: “Your children are just on loan to you. They are with you a short while; then they leave to take on lives of their own.” And, when I questioned her, she would say, “You’ll see, honey! One day you will understand.” I did, I do, and now I know how wise she was. However, the joy of knowing and loving my son’s family—including my two granddaughters—has more than compensated.

Career and Retirement

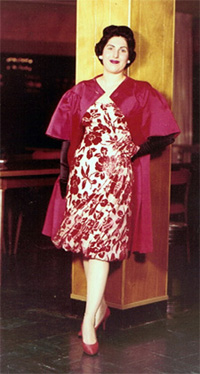

Coat and dress, designed by Jewel Littenberg, about 1960. After our son was born, we decided to move out of the city, and for almost 10 years, I was a stay-at-home mom. One day while I was shopping, an appliqué-adorned tennis skirt caught my eye. Although I had never designed tennis skirts, it brought back memories of the hundreds of appliques I had created through the years. Curious to see if I still had what it took to be a designer, I decided to invest $100 in some fabric and whip up a few samples. I set up shop in our sun room, and within a matter of weeks, I began selling to local golf and tennis shops, as well as small stores. Within a few months, I outgrew the sun room and rented my first warehouse space, and the business progressed from there. Within a short time, I had employed several people, including eight salespeople, and in addition to the pro shops, I was selling to major department stores, such as Saks Fifth Avenue, and also to stores in Japan and South America. Eventually, we constructed our own building, and I also opened a retail outlet. The business lasted for 23 years; I felt the pinnacle was reached when I was chosen to be in the 1987–1988 edition of Who’s Who in American Women for my achievements in the field of fashion. All because of curiosity and a $100 investment . . .

Career Interruptus

Jewel’s father, Haskell Goldstein, in 2004. A few years prior to my retirement, my mother had her first stroke, the beginning of a downward spiral, and I oversaw her home care for the next few years. When she died, my father was 87 and in excellent health. However, at the age of about 90, although still in good health and living in his home, he started to need some additional help. What began with an hour or two a day eventually became a 24/7 situation that required a live-in caregiver for the remaining seven years of his life. It was about this time that I decided to retire so I could spend every day with him. My father had chosen to care for my mother at home, with my assistance, and so her private care did not create a financial burden. Nor did the first few years of my father’s decline. However, as time went on and Dad came to require a live-in aide, his Social Security checks and minimal savings were rapidly depleted. His prospects for continuing to live in the way best suited to him looked grim. I began to realize the difficulties faced by a person in deciding whether to remain in his or her own home and age with dignity . . . and I also began to think about what I could do—not only for my father but for everyone in that situation. I paid more attention to newspaper articles about elderly people living alone who would “raise the shade” to let the neighbors know they were okay, and still others all alone who didn’t even have that advantage. In addition, I became more aware of nursing home abuse cases and mistreatment by in-home caregivers. I felt that something had to be done.

Advocate for the Elderly So, in 1999, I began to write a proposal asking that the same government funding for nursing home placement be provided for in-home care. I also requested more extensive training and supervision for home health aides and certified nursing assistants. I planned to seek signatures of support and to send them to our elected officials in Washington. I asked newspapers to write about what I was doing, and I offered to speak to clubs and organizations about care for the elderly. In addition, I contacted state and U.S. senators and congressman, and convinced them to hold town hall meetings. I also got in touch with local towns and cities, and won their endorsements, as well. My proposal caught on, and almost everyone I had asked for help was more than willing to do so. Soon, I became known as an advocate for seniors—even to the point of being nominated as “advocate of the year” for the state of Florida. Although I did not win, I still regard the nomination as a great honor.

Jewel preparing to broadcast at WPBR. After my father’s death, I continued to advocate. I wrote, hosted, and produced talk show programs for both radio and television, during which I interviewed experts who spoke and took phone calls on numerous topics pertaining to the elderly. These shows, aired 2002–2004 by WPBR Radio in Florida and on TV by The Education Network, were originally called Issues and Answers with Jewel and later Issues, Answers, and More . . . with Jewel. I paid for the radio show myself, and when I left to go with The Education Network, the radio program was being considered for syndication.

"Dorothy," an oil painting by Jewel Littenberg. In addition, for the past 10 years I have been working to launch a home shopping program for the frail elderly and disabled. A major supermarket chain is interested, and the pilot is ready to go. I have contacted numerous local churches, foundations, and other organizations for funding. All think it is a great idea and desperately needed service. However, nobody has the available monies. But, I am optimistic that one day this, too, will become a reality.

Life—Forever an Adventure I approach life as an adventure and can never remember not wanting to live each day as though it were my last. I have won many awards and much recognition as both an artist and a designer. However, if I could choose a lasting legacy, it would be my efforts, my determination, to make a difference in the lives of the elderly. LINKS

www.opencongress.org/bill/111-hr271/blogs?sort=toprated

thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d111:H.Res271:

https://www.popvox.com/bills/us/111/hres271

www.encore.org/old/user/jewel-littenberg

seniorjournal.com/NEWS/Opinion/4-11-05JewelLittenberg.htm

Jewel Littenberg is a NYC fashion designer and retired resident of the state of Florida. Her post–empty-nesting “job” is advocating for the elderly. Jewel can be reached at jed472@bellsouth.net with questions about or support for issues concerning our oldest relatives, neighbors, and friends. Jewel Littenberg is a NYC fashion designer and retired resident of the state of Florida. Her post–empty-nesting “job” is advocating for the elderly. Jewel can be reached at jed472@bellsouth.net with questions about or support for issues concerning our oldest relatives, neighbors, and friends.

|

Empty Nest: A Magazine for Mature Families

© 2011 Spring Mount Communications